The Perils of Photography at Point Lookout-R.M. Linn

by Jeffrey Kraus & Bob Zeller

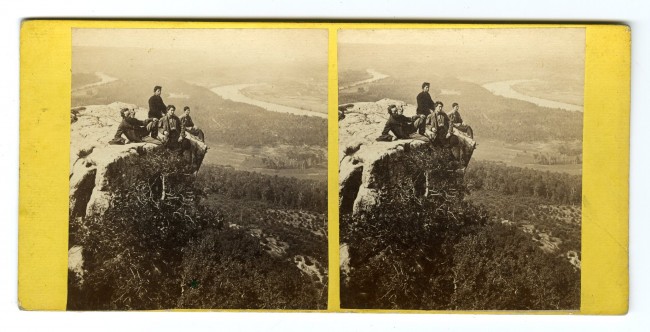

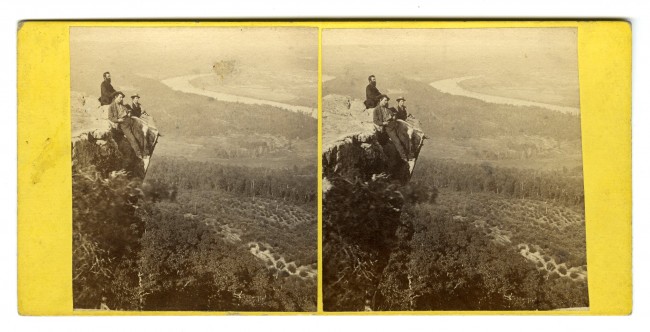

Almost 2,000 feet above the Tennessee River, a distinctive rock promontory juts out of Lookout Mountain known as Point Lookout.

The precipice looks down on the winding river as it passes Chattanooga, providing one of the most spectacular vistas anywhere in the United States. It was here in late 1863 that Robert “Royan” M. Linn established a photo studio and began taking photographs by the hundreds of Union officers and soldiers posing on Point Lookout.

Linn gained access to the site shortly after Union forces took the mountain on November 24, 1863 in what became known as the “Battle Above the Clouds.” Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted the mountain and defeated the outnumbered Confederate defenders commanded by Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson.

It was a small engagement, but the Union forces drove the Confederate left flank, allowing Hooker’s men to assist in the famous assault on Missionary Ridge the following day, which routed the Confederate Army of Tennessee commanded by Gen. Braxton Bragg and opened the gateway to the Deep South.

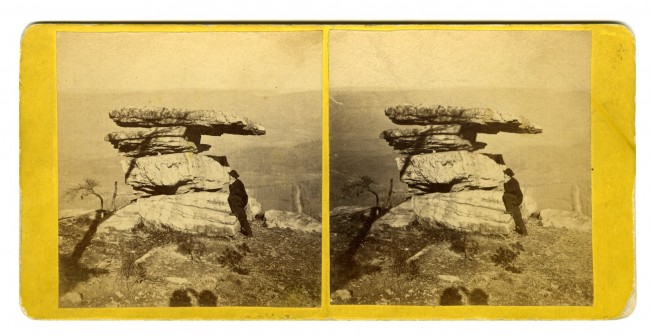

Soon after Union forces captured the famous mountain, Linn, an enterprising Ohio photographer, arrived and found himself with two breathtaking new places to ply his trade – Point Lookout and nearby Umbrella Rock.

Linn nailed together a studio just behind Point Lookout and named it “Gallery Point Lookout.” With his brother, J. Birney Linn, he began taking photographs in December 1863. The Linns almost immediately found themselves the proprietors of a tremendously lucrative business, photographing officers, soldiers and civilians posing at the point.

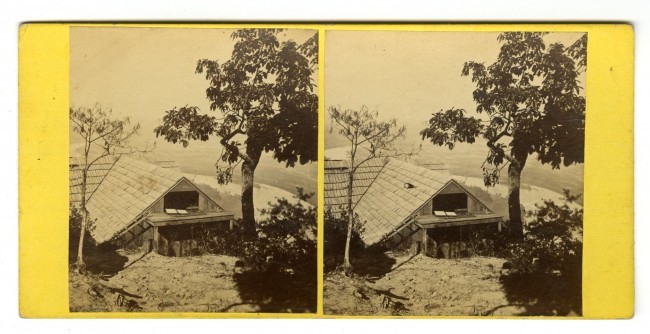

In the late afternoon, the stereo camera captures a side view of Linn’s Gallery Point Lookout studio on Lookout Mountain.

Today, we have an intimate look at one of the most fascinating photographic operations of the Civil War because of a small group of stereo views that Linn took to document his presence there, and from the diary of Union surgeon James Theodore Reeve, who was stationed near the Point and wrote about the photography in several of his entries.

As Reeve documented, the scenic rock outcropping was a dangerous precipice, and death would pay a visit in 1864, along with an accidental near-poisoning. Reeve’s writings and Linn’s stereo views together provide one of the finest accounts of any Civil War photography studio.

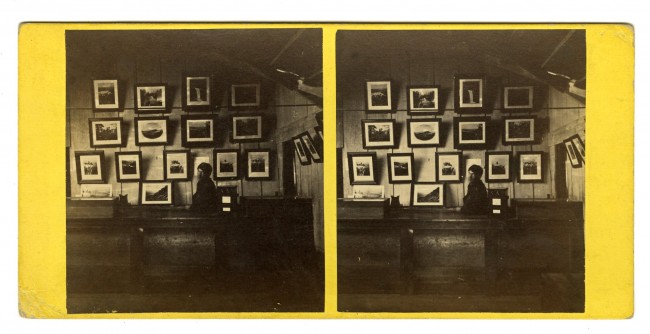

In the early 1990s, Jeffrey Kraus obtained five of the stereo views that illustrate this article when he acquired the photographica collection of renowned stereo collector Gordon Hoffman. Two views show the exterior of the studio; one view shows the interior and the front desk, on which sits a Beckers viewer to the right and a Brewster viewer towards the left; and two views show the staff photographers posing on Point Lookout.

At the time, Jeff decided to keep only one of the views, the interior of the studio, and sell the others, which he did to Tex Treadwell. Tex passed away several years ago and his vast collection of stereo views was consigned to John Saddy’s stereo view auction and has been gradually sold over the years. In late 2011, Jeff noticed a group of Point Lookout views in Saddy’s auction with “notations on verso in an unknown hand.”

As Jeff quickly saw, some of the “notations” from an “unknown hand” were his own from years earlier, and he was excited to have the opportunity to reunite with the five views. As a comment on our economic times, Jeff was able to acquire them for less this second time around, even though some 20 years had passed.

This magnificent stereo view shows the interior of Linn’s Gallery Point Lookout with a clerk behind the counter, which holds both a Beckers-style and a Brewster viewer. Behind the clerk, the wall is filled with images from Lookout Mountain, including shots of Lulu Lake and several photographs of Union officers posing at Point Lookout.

A few months later, Jeff was able to acquire from fellow dealer David Spahr two more Linn stereo views showing Umbrella Rock that were taken at different times, including one showing Royan Linn himself posing next to what appears to be a photography shack he built at that location.

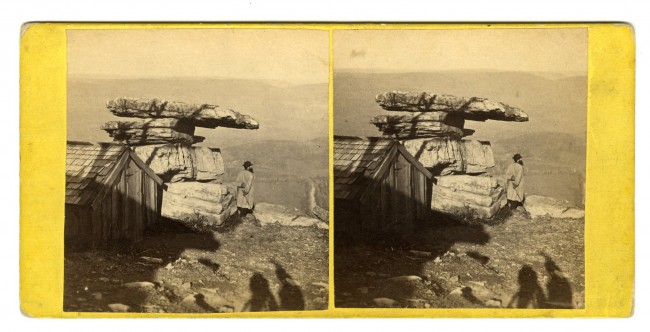

In this iconic stereo portrait from Lookout Mountain, the image captures the shadow of the photographer exposing the plate that shows photographer Royan M. Linn posing at Umbrella Rock near his photography shack there.

The Linns took large-format photographs, stereo views, tintypes and cartes de visite. Some of the large-format images are visible on the back wall of the stereo photograph of the studio’s interior. Stereo views were labeled as “Photographic Mementoes of Lookout Mountain.” A wartime Linn label advertised 13 different 3-D scenes, including images of Gen. George Thomas and Gen. Joseph Hooker at Point Lookout.

The Linns, like most Civil War photographers, left little in the way of written information. Their legacy is their images.

But Union surgeon Reeve was stationed on Lookout Mountain for more than two months in early 1864, and the presence of the nearby photography studio made its way into his diary on several occasions.

January 21, 1864 was a “beautifully warm Spring-like day” on Lookout Mountain that was suddenly interrupted by “quite an interesting little incident,” Reeve wrote in this excerpt from James Theodore Reeve: Surgeon. Soldier. Citizen. 1834-1906-A Civil War Commentary, compiled and annotated by Ann Wartinbee Reeve in 1999, and provided courtesy of James H. Ogden III, National Park Service historian at Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park.

Reeve and another doctor were both reading in their office when “we heard rapid steps on the Piazza, and an excited rapping at the door of the steward’s room, which was immediately opened by someone who was evidently in great haste.”

Reeve went to see what was up and found himself facing a very agitated Capt. C. A. Catlin, an inspector general in the 11th Corps.

“Doctor, give me an emetic, quick!” Catlin said. “I am poisoned by having taking Cyanide of Potassium.”

“Are you certain of that, captain?” Reeve asked.

“Yes,” he said. “By mistake. At the ambrotype saloon.”

A skylight is open at Linn’s Gallery Point Lookout studio, exposing to the sunlight what appear to be plate holders for making prints.

As Reeve quickly prepared the solution, he learned more.

Although fresh water was apparently abundant at Point Lookout, with Royan Linn reporting that he had “free use of a clear, crystal spring that bursts from the brow of ‘Old Lookout,’” the thirsty captain obviously didn’t find that source. Instead, he spotted a pail of water and asked the camera operator if it was drinking water. “Yes,” said the operator.

Next to the pail, the captain saw a small, wide-mouthed bottle. Thinking it was a drinking cup, he dipped it into the pail. He swallowed two or three mouthfuls before a bitter taste filled his mouth. Only then did he learn the bottle contained a solution of Cyanide of Potassium for preparing photographic plates.

Catlin jumped on a horse and hurried to the surgeons’ quarters, trailed by three or four other worried officers.

“Fortunately for him, the solution was evidently too weak to produce serious consequences, and the emetic was probably really unnecessary, though very proper,” Reeve wrote. “After so thoroughly emptying his stomach with our nostrums, we could do nothing else but invite him to fill it again at our table, which he did with a friend of his, a German lieutenant.”

Reeve himself had his photograph taken at the point that very day, as well as two days later, on Jan. 23, and again on Jan. 25, even though he was annoyed by the prices. “Crowds are constantly being ambrotyped at the point, the operator charging the enormous price of $3 per picture, which I regard as an imposition on the soldiers,” he wrote.

It is likely that the “operator” Reeve speaks of is Linn or one of his photographers and that “ambrotype saloon” is Linn’s wooden studio, but that cannot be firmly documented, and there are reports that other photographers worked at Point Lookout, possibly independent of Linn.

By March 18, 1864, Reeve had moved to Tyner’s Station (now a part of the city of Chattanooga). There, he received by mail some shocking news from up on Lookout Mountain.

A group of photographers, possibly including Royan M. Linn at left, pose for Linn’s stereo camera at Point Lookout in this image taken during the war or shortly afterwards.

“Roper, the ambrotype artist on the mountain, fell from the rock yesterday and was instantly killed, the fall breaking his neck,” Reeve wrote.

Again, whether Roper worked for Linn (and possibly appears in the imagery of the photographers) or whether he was an independent operator is unknown. The story becomes even more fascinating in light of the fact that Point Lookout became known as Roper’s Rock, but was said to have been named not after an unfortunate photographer, but a Pennsylvania corporal who fell to his death.

By the 1870s, stereo views issued at Gallery Point Lookout featured the backmark of J.B. Linn and listed 44 different views of Lookout Mountain for sale, including The Great Flood of 1867. After Royan Linn died in 1872, J.B. Linn continued to operate the lucrative business until 1886. These postwar J.B. Linn views were very popular, because examples are common in today’s antique photo market.

In this stereo view, photographer Royan M. Linn poses behind two of his photographers or assistants at Point Lookout, where he established a lucrative photographic business in December 1863 that flourished for more than 20 years.

When the soldiers went home, they took with them their pictures from Point Lookout, and their stories about the magnificent views. The word spread, and Lookout Mountain became one of the most popular tourist attractions in the country and the world, in part because of its distinction of possibly being perhaps the single most photographed spot in the United States during the Civil War.

This Linn stereo view of Umbrella Rock was taken at exactly the same spot as an earlier view illustrated above that shows Linn, but at a distinctly different time, mostly likely after the shack was removed. The shadow of the photographer can be seen.

All images from the Jeffrey Kraus Collection.

This article appeared in Stereo World as well as the newsletter of The Center for Civil War Photography.

Len Walle

June 30, 2012 @ 12:08 pm

It’s great to see the interior view of Linn’s Gallery Point Lookout (a real stunner), especially after it was inadvertently left out of the article that was published in StereoWorld. I have a half-plate tintype of a group on Point Lookout that I need to share with you.