LOU3. No ID. No. 52. Canal St. North from Camp. G+. $75

LOU47. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Levee, N.O. VG. $65

LOU52. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 668. Swamp Scenery. VG. $45

LOU57. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 414. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 5. Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking North. G. $75

LOU85. No ID. Canal St. to Christ Church. Stamp on verso “From M. Miller, Dealer in Photographs, Stereoscopic Views, Etc. 7 Charles St.” VG. $175

LOU115. Walker & Mancel. St. James Parish, from Grand Point. G. $20

SH153. S.T. Blessing. Levee and River Views. No. 111. Red River Steamboat Landing. Cotton Bales on the Levee. This is the Steamboat “New Era.” VG. $125

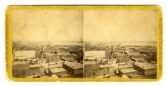

LOU119. No photographer ID. Views in New Orleans. Panoramic View. G. $65

LOU121. W.H. Leeson, New Orleans. Canal St. The photography gallery of William H. Washburn can be seen behind and just to the left of the statue. G. $150

LOU122. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 410. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 1, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking South. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. G. $125

LOU124. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 412. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 3, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking West. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. G. $125

LOU125. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 413. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 4, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking North-West. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. VG. $150

LOU126. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 414. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 5, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking North. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. G. $125

LOU128. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 416. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 7, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking East, showing the River, McDonoghburg, and the River again in the distance. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. G. $125

LOU129. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Views of New Orleans, No. 417. Bird’s-Eye Panoramic View, No. 8, Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking South-East, showing the River and Gretna in the distance. This View, with seven others, Nos. 1 to 8, or negatives 410 to 417 inclusive, forms a Panorama of the whole City. G. $125

LOU130. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Inundation of New Orleans, 1868. Trimmed at right margin. VG. $250

LOU131. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Inundation of New Orleans, 1868. G. $175

![]()

LOU132. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. Note from a previous owner of this view: “Exceedingly Rare. Building on far right is “Harvey Castle” on West Bank of Miss.” G. $175

LOU133. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 201. Algiers Dry Dock. E. $200

![]()

LOU135. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 29. Levee and Steamboat Landing. Looks like one can see the shadow of the photographer at right. VG. $150

LOU137. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. Levee, foot of Bienville Street. VG. $150

LOU138. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 202. Towboat Station, Algiers. VG. $175

LOU139. No photographer ID, probably Theo. Lilienthal. Untitled levee with barrels and cotton, houses at left. Note on verso indicates that this view is “ex-Darrah Coll.” E. $150

![]()

LOU140. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 29. Levee and Steamboat Landing. This is the same title as Lou135 above but an entirely different scene. The shadow of the photographer is clearly seen at bottom. VG. $175

LOU141. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 660. Live Oak and Palmettoes. G. $75

LOU142. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. 604. Bonzano’s Residence, Chalmette. VG. $75

LOU143. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. 670. Duck Hunting, Cypress Lake. VG. $100

LOU145. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. 750. Lake Pontchartrain. G. $85

LOU146. Henry Mancel. Moss Trees. VG. $85

LOU148. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Bayou Rouge. G. $85

LOU149. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Indian Church. Card trimmed top and bottom. G. $75

LOU150. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. Grand Lake in Summer. Avery Ellis Parish. VG. $100

LOU151. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 50. Canal St., west from Clay Statue. G. $100

LOU152. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 70. Custom House and Post Office. The smoke above is from the steamboats at the levee. VG. $125

LOU153. [Mugnier, New Orleans.] No. 64. Canal St. South West from Chartres St. G. $85

LOU154. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 53. Canal St., east from Camp St. The smoke above is from the steamboats at the levee. VG. $125

LOU155. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 72. Camp St. & St. Patrick’s Church. VG. $125

LOU156. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 385. Entrance of the Bazar, French Market. G. $150

LOU157. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 432. Madame John’s Legacy, Dumaine Str. Madame John’s Legacy is located in the historic French Quarter. It is one of the finest 18th-century building complexes in Louisiana and one of the best examples of French colonial architecture in North America. Built in 1788 following a devastating fire that destroyed eighty percent of the city, it was constructed in the French colonial style that prevailed before the disaster. Madame John’s is an excellent example of Louisiana-Creole 18th century residential design. Due to its fine architectural character and historical significance, it is an official National Historic Landmark. The complex consists of three buildings—the main house, a kitchen with cook’s quarters, and a two-story dependency. The house’s name was inspired by George Washington Cable’s 1874 short story “‘Tite Poulette,” in which the character Monsieur John bequeaths a Dumaine Street house to his mistress, known as Madame John. Though older parts of town were once dotted with similar structures, today very few houses like Madame John’s Legacy remain. G. $200

LOU159. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 58. Lee Monument. The Robert E. Lee Monument formerly in New Orleans is a historic statue dedicated to Confederate General Robert E. Lee by noted American sculptor Alexander Doyle. It was removed (intact) by official order and moved to an unknown location on May 19, 2017. Any future display is uncertain.

Efforts to raise funds to build the statue began after Lee’s death in 1870 by the Robert E. Lee Monument Association, which by 1876 had raised the $36,400 needed. The association’s president was Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Charles E. Fenner. New York sculptor Alexander Doyle was hired to sculpt the brass statue, which was installed in 1884. The granite base and pedestal was designed and built by John Ray [Roy], architect; contract dated 1877, at a cost of $26,474. John Hagan, a builder, was contracted to “furnish and set” the column at a cost of $9,350. The monument was dedicated in 1884, at Tivoli Circle (since commonly called Lee Circle) on St. Charles Avenue. Dignitaries present at the dedication on February 22—George Washington’s birthday—included former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, two daughters of General Lee, and Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. The statue itself rises 16’6″ tall, with an 8’4″ base, standing on a 60′ column with an interior staircase, according to a schematic released by the City of New Orleans on the day of the removal of the statue and its base, May 19, 2017. The Lee statue faced “north where, as local lore has it, he can always look in the direction of his military adversaries.” In January 1953, the statue of General Lee was lifted from atop the column for repairs to the monument’s foundation. The statue was returned to its perch in January the following year. A racial confrontation occurred at the monument on January 19, 1972, the birthday of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, when Addison Roswell Thompson, a perennial segregationist candidate for governor of Louisiana and mayor of New Orleans, and his friend and mentor, Rene LaCoste (not to be confused with the French tennis player René Lacoste), clashed with a group of Black Panthers. Then eighty-nine years of age and a former opera performer in New York City, LaCoste was described as “dapper in seersucker slacks and navy sports jacket” and with a “white mustache and goatee” resembling Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken. LaCoste and Thompson dressed in Klan robes for the occasion and placed a Confederate flag at the monument. The Black Panthers began throwing bricks at the pair, but police arrived in time to prevent serious injury. At the time of the Thompson/LaCoste confrontation, David Duke, then an active Klansman who served from 1989 to 1992 in the Louisiana House of Representatives, had been among those jailed in New Orleans for “inciting to riot.” G. $85

LOU160. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 707. Moonlight, Gulf of Mexico. VG. $75

LOU162. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 84. Pickwick Club. VG. $100

LOU163. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 152. Restaurant, West-End. G. $75

LOU164. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 140. Moresque Building. Cast iron building. VG. $100

LOU169. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 155. Opera House, Spanish Fort. G. $85

LOU170. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 100. Hotel, West-End. G. $65

LOU172. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 60. Christ Church. G. $65

LOU174. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 230. Scene at the French Market. G. $175

LOU175. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 92. Old Spanish House, Chartres St. G. $175

LOU176. [S.T. Blessing, New Orleans]. No. 408. Tiled-Roof House, St. Peters Str. G. $200

LOU177. [S.T. Blessing, New Orleans]. No. 144. City Hall. G. 475

LOU178. H. Mancel. French Market. G. $100

LOU179. Mugnier, New Orleans. No. 79. Margaret’s Place. New Orleans Female Orphan Asylum. G. $125

LOU180. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 210. View Cotton Levee. G. $75

LOU181. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 222. Moonlight on the Mississippi. G. $75

![]()

LOU183. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. Steamboat Levee. G. $75

![]()

LOU184. Lilienthal & Co., New Orleans. Levee opposite French Market. G. $75

![]()

LOU185. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 30. Levee and Upper Landing. G. $75

![]()

LOU186. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 31. Levee and Steamship Landing. G. $75

![]()

LOU188. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. Interior of Steamer Frank Pargoud. This sidewheel, wooden hull packet was built in 1868 by Howard & Co., Jeffersonville, Indiana. The FRANK PARGOUD was built for John W. Tobin, of New Orleans, who was the sole owner, and it was named for Gen. Frank Pargoud, a wealthy Ouachita River planter. Originally designed for the New Orleans-Ouachita River trade, she proved too large and was placed on the New Orleans-St.Louis trade, running several trips. She subsequently ran between New Orleans-Memphis, making weekly round trips, which was an achievement for a regular packet. Later, she was moved to the New Orleans-Vicksburg trade, running two trips per week, before running steadily in the New Orleans-Fort Adams trade. G. $75

LOU193. No photographer ID. Launch of the Nucleus, N.O. La. 1899. VG. $25

LOU196. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 521. The Fountain, Canal Street. E. $200

![]()

LOU197. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 45. Charles Street, Showing Masonic Hall. Other signs visible on street such as “Gun Store.” E. $200

![]()

LOU198. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 101. Clay Statue, Crescent Billiard Saloon and St. Charles Hotel. “Photographs” sign to the left of Clay. VG. $150

![]()

LOU199. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 104. Flood in July 1871, Claiborne Street. VG. $150

LOU200. S.T. Blessing, New Orleans. No. 411. Bird’s-eye Panoramic View, No. 2. Taken from St. Patrick’s Church Spire, looking South-West. VG. $150

![]()

LOU201. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 14. U.S. Customhouse, Canal Street. VG. $100

![]()

LOU203. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orleans. 4. Interior of St. Mary’s Church, Josephine Street. VG. $45

![]()

LOU205. Theo. Lilienthal, New Orlearns. 2. Cypress Grove, or Firemen’s Cemetery. Foot of Canal Street. G. $35

![]()

LOU209. Theo. Lilienthal, 45. St. Charles Street, showing Masonic Hall. VG. Sign for “Boots and Shoes made on Anatomical Lasts.” $150

![]()

LOU213. New Orleans, La. The Mississippi River. No. 14. Canal Street Ferry Boat Louise. VG. $40