The Burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum, NYC

by Jeffrey Kraus

There was great bias against immigrants as well as virulent racial hostility in New York City in the 1830’s. Public schools were segregated, blacks were not permitted seats in cabins on Hudson River steamers but had to ride on deck no matter how bad the weather, white churches segregated blacks in separate pews, etc. While there were a number of white supporters, inevitably blacks were subjected to violence.

Beginning on July 7, 1834 in NYC, four nights of anti-abolitionist riots beset the black community and their friends. Black and abolitionist merchants were target for attack and the homes of abolitionist brothers Arthur and Lewis Tappan were sacked. Black men married to white women were attacked. Causes of such atrocities on the part of hundreds and thousands of citizens are always multifaceted, this being no exception. The forces of nativism, abolitionism and its opponents, and the fear and resentment towards blacks from the Irish underclass and other immigrants in the highly segregated yet mingled Five Points district all played a role in the violence.

This was the climate in which the Colored Orphan Asylum was established. In line with the white paternalistic standards of the time, it was white women who established the orphanage. The black community at the time had few educated individuals and a lack of individual and collective wealth. The fact that white women ran the institution permitted it to avoid the politically charged issue of social equality.

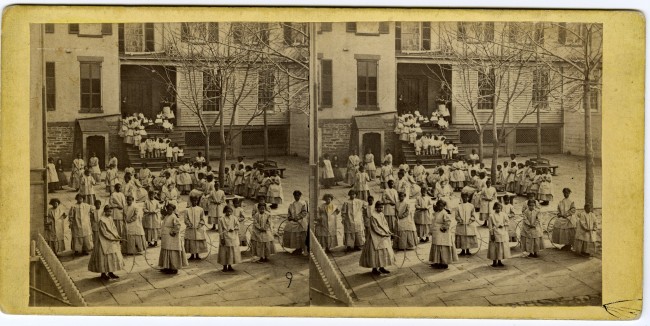

Boys’ Play-ground, Colored Orphan Asylum

The Colored Orphan Asylum was formed in November of 1836 and they could not find space to rent to care for black orphans. They decided to purchase a building which they did, located on Twelfth Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in Manhattan. By June of 1837, eleven children rescued from almshouses were living there. The early years were difficult both financially and in developing relationships with the black community.

On May 1, 1843, the orphanage moved to their new home on 43rd St. and Fifth Ave. which is where, during the Civil War, it faced its greatest existential crisis as it was totally destroyed by mob violence in July 1863.

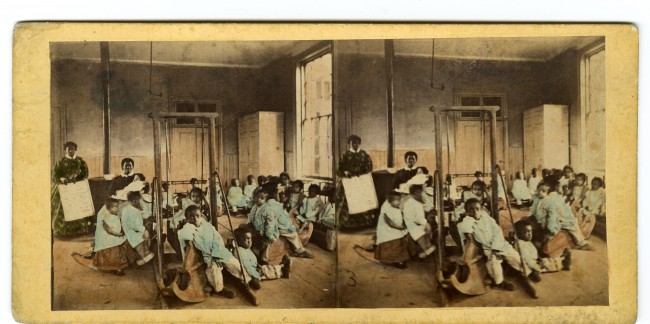

Untitled tinted view of playroom with boys and girls, Colored Orphan Asylum.

Approximately 12 children entered the orphanage during the Civil War because their fathers had been killed in battle or because their absence had made it difficult for their mothers to care for them. Some prior residents of the asylum went on to fight for the Union. One, James Henry Gooding was born a slave in 1838 in North Carolina; his freedom was purchased by James Gooding, possibly his father, and he came to NY. He entered the orphanage on Sept. 11, 1846, and remained for 4 years. After several whaling voyages out of New Bedford, Gooding enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Company C on February 14, 1863. He wrote 48 letters that were published in the New Bedford Mercury between March 3, 1863 and Feb. 22, 1864. His most famous letter was addressed to Abraham Lincoln on Dec. 28, 1863 advocating for equal pay for black soldiers. He was promoted to corporal in December, 1863. He was wounded in the battle of Olustee, Florida, on February 20, 1864 and captured. He died in captivity in the notorious confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Ga., July 19, 1864.

The NYC draft riots which occurred from July 13 to July 16, 1863 were the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War itself. Regiments of militia and volunteer troops had to be sent in by Lincoln to quell the mobs.

Again many causes led to the violence. The new draft laws passed by congress unfairly affected poor, working class men as they could not afford the $300 to hire a substitute. The Irish and the blacks were often competing for the same menial jobs and there was great tension between the groups.

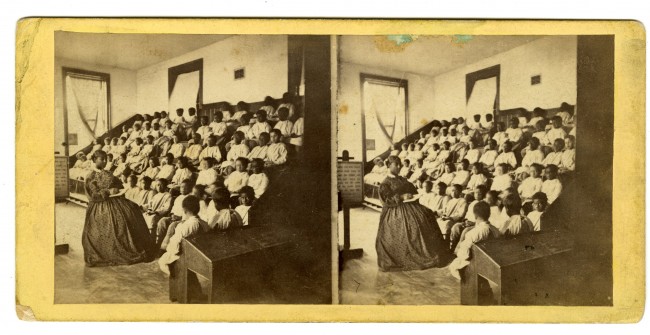

The Colored Orphan Asylum was targeted as it was viewed as an example of how New York’s upper class spent their money favoring blacks over the Irish. The young orphans had plenty to eat, clean beds to sleep on, and were provided an education. On the day the orphanage was burned to the ground, there were 233 children in residence. It is almost certain that some of those children are pictured in the 4 rare stereoviews accompanying this article. We do not know who the photographer was of these images but they are certainly produced prior to the draft riots, probably circa 1860. If anyone has other such images of the Colored Orphan Asylum, either interiors or exteriors, or any information as to the photographer, the author would be most interested in hearing about it.

Infant School, Colored Orphan Asylum

There is much information available on the internet as well as in publications on the details of the events of the day of the burning. In the end the children escaped to a police station on 35th St. where they remained for several days. On July 16th, under guard of Zouaves and police, the children were transported to Blackwell’s Island (today, Roosevelt Island) where they remained into the fall of 1863. A temporary home for the children was established at the former home of Hickson Field in the hamlet of Carmansville on the upper west side of Manhattan at 150th St. and Broadway. While it was ill-suited and in quite a state of decay, it remained the site of the orphanage until May 1868 when they relocated to their new site at 143rd and Amsterdam Avenue in undeveloped Harlem where they remained until 1907. The final move was to 261st and Palisade Avenue in the Riverdale section of the Bronx.

Under various societal and legal pressures far beyond the scope of this article to discuss, the Colored Orphan Asylum changed it name to the Riverdale Children’s Association in Feb. 1944. The admission of white children also began around that time. Of course, in addition, there were enormous changes in the way children in need of social welfare services were cared for. There was growing disapproval of orphanages and the transition had to be made to serving children in foster care. The Riverdale property was sold but the Riverdale Children’s Association, through a series of mergers, is now alive and well and operating as the Harlem Dowling-West Side Center for Children and Family Services. This organization is still carrying on the vital work begun so long ago by the brave founders of the Colored Orphan Asylum. I encourage you to visit their website and to support them: http://www.harlemdowling.org.

Girls’ Play Ground, Colored Orphan Asylum

References:

Seraile, William. Angels of Mercy: White Women and the History of New York’s Colored Orphan Asylum. NY: Fordham University Press, 2011.

Wikipedia.

All images from the Jeffrey Kraus Collection

Jimmy Leiderman

June 14, 2012 @ 12:36 pm

Congrats on the new website design and here’s hoping to read more interesting blog posts in the future.

Long time since I last bought something, but I keep coming back to check if you’ve added any sports related cdv’s or stereoviews.